The haunting melodies of ancient Greece still echo through the corridors of Western music, whispering secrets of a civilization that first dared to organize sound into mathematical beauty. Long before Bach composed his fugues or Beethoven unleashed his symphonies, the Greeks were experimenting with scales, modes, and the very physics of vibration. Their musical legacy forms the bedrock upon which our entire Western musical tradition stands - not merely as historical curiosity, but as living DNA in the music we create today.

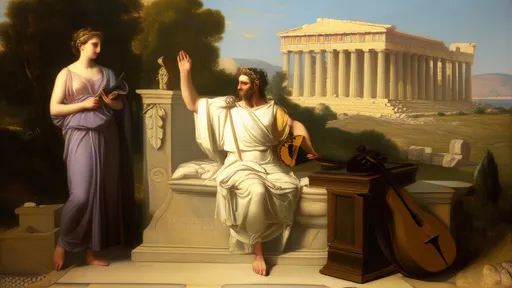

Imagine the lyre of Orpheus, its strings vibrating in the smoky air of an Athenian symposium. This was no mere entertainment, but a sacred art form intertwined with philosophy, mathematics, and cosmology. The Greeks didn't separate music from the study of the universe - Pythagoras discovered musical intervals while experimenting with vibrating strings, realizing that consonant sounds emerged from simple mathematical ratios. This revelation that numerical relationships governed pleasant sounds became the foundation of Western music theory, a truth that still guides composers in the 21st century.

The Greek musical system revolved around modes rather than the major-minor scales we know today. These modes - Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, and others - each carried distinct emotional flavors and ethical associations. Plato himself argued in his Republic that certain modes strengthened moral character while others encouraged decadence. The Mixolydian mode's solemn dignity accompanied religious ceremonies, while the passionate Phrygian mode stirred warriors before battle. Centuries later, medieval church musicians would adapt these very modes into the Gregorian chant that dominated European sacred music for a thousand years.

Remarkably sophisticated instruments emerged from Greek workshops. The aulos, a double-reed wind instrument, could produce haunting microtonal melodies that modern ears might find startlingly avant-garde. The kithara, a concert lyre, featured precisely calculated string lengths to achieve perfect intervals. Hydraulis, the world's first pipe organ powered by water pressure, astonished audiences in amphitheaters with its powerful sustained tones. These weren't primitive noisemakers but carefully engineered devices that allowed professional musicians - highly respected in Greek society - to explore the frontiers of sonic possibility.

Greek musical notation, preserved on fragile papyri and stone inscriptions, reveals compositions of startling complexity. The Seikilos epitaph, dating from the 1st century AD, survives as the oldest complete musical work with both notation and lyrics. Its melancholic melody, accompanying a poem about the fleeting nature of life, demonstrates an advanced understanding of musical phrasing and emotional expression. Modern reconstructions of ancient Greek music often surprise listeners with their unfamiliar tonal colors - neither quite Eastern nor Western to contemporary ears, yet undeniably sophisticated.

Theater provided the most spectacular showcase for Greek musical innovation. In the great tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, the chorus moved and sang in carefully measured rhythms, their words enhanced by the enharmonic genus - a microtonal scale system that allowed for quarter-tone intervals. This created an otherworldly atmosphere that modern experiments with microtonal music strive to recapture. The dithyramb - ecstatic choral songs honoring Dionysus - blended poetry, dance, and music into what we might recognize today as a precursor to opera.

Greek musical theory traveled through Roman adaptations into the medieval world, where it shaped the development of Christian liturgical music. Boethius' De institutione musica, heavily influenced by Greek thought, became the standard music textbook in European monasteries for centuries. The eight church modes of medieval chant directly descend from Greek modal theory, filtered through early Christian theologians who saw in music a reflection of divine order. Even the word "music" itself comes from the Greek "mousike," meaning the art of the Muses - originally encompassing poetry, dance, and what we now call music as a unified expression.

Modern musicians continue to rediscover Greek musical concepts with fresh ears. Jazz musicians explore modes that would have been familiar to any ancient Greek music student. Contemporary composers experiment with just intonation systems based on Greek mathematical principles rather than the equal temperament we've grown accustomed to since Bach. Even popular music occasionally taps into this ancient well - the distinctive "Greek blues" scale used in rebetiko music or the modal harmonies of certain film scores consciously evoke those ancient melodic patterns.

The next time you hear a simple major chord, remember that its pleasing sound was first mathematically demonstrated by a Greek philosopher experimenting with a stretched string. When a film score uses a haunting minor mode to signal tragedy, it channels emotional associations the Greeks established millennia ago. Our very conception of music as both mathematical science and emotional art remains fundamentally Greek at its core. The melodies may have evolved, but the foundation remains unshaken - a testament to the extraordinary musical imagination of ancient Greece.

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025